- Showcases how to build a Battleship game on Ethereum using a lightweight cryptographic technique for hidden coordinates.

- Stores hashed ship positions as ECDSA signatures so only the owner can prove hits or misses.

- Demonstrates verifying these signatures on-chain to ensure game fairness and incomplete information.

- Provides a complete Solidity contract and tests with Hardhat for a two-player Battleship match.

Main article

Zero-knowledge proof is a method by which one party (the prover) can prove to another party (the verifier) that they know a value, without conveying any information apart from the fact that they know the value. This concept is commonly used in zero-knowledge chains that are becoming more common in the blockchain ecosystem lately. This article will guide you through how you can develop a blockchain game using this principle.Learn more about zero-knowledge based blockchains by reading zkEVM and zkRollups Explained.

What is battleship

Battleship, a guessing game played between players on separate grids representing their fleets of ships. Each player has their own grid and they place their ships on the grid in secret. The objective of the game is to sink the opponent’s fleet of ships by correctly guessing the locations of their ships on the grid. Players take turns calling out coordinates, any(x,y), on the opponent’s grid, in an attempt to find the location of the opponent’s ships. If a player guesses a coordinate where a ship is located, the opponent must respond with “hit”. If a player guesses a coordinate where there is no ship, the opponent must respond with “miss”. The player who sinks all of their opponent’s ships first wins the game.

What we’ll be doing?

In this tutorial, we’ll be building our very own game of battleship on Ethereum. There is a slight hitch however. Battleship is a game of incomplete information, and that doesn’t sit nicely with the public, permissionless nature of Ethereum (and other public blockchains like Polygon). While we can declare state variables as private, anyone could still access their values. How do we store private data on a public blockchain? It’s a catch-22, or is it?Our approach

There are multiple approaches to privacy on the blockchain thus far. One particularly promising one has been ZKPs (zkSNARKs, zkSTARKs etc.). However in this tutorial, we’ll be going lightweight. We need to a create a unique identifier for each players ship’s coordinate that would be impossible to guess/reverse by anybody else, but which can be verified in the future, to reveal the initial data (ship’s coordinate). We need a one-way function, and public-private signatures are a perfect match for this use case. Public-private signatures are also known as digital or cryptographic signatures. It is the same technology behind authorizing transactions on the blockchain. We sign an arbitary byte of data (a ship coordinate in this case) with our private key, and this generates a signature. We can then retrieve the corresponding public key/address of a signature and confirm if it matches the expected value. Signing a message with a private key is deterministic, meaning signing the same data with the same private key will always produce the same signature. Here’s a brief overview of how it all fits together:- Player1 signs their ship coordinates and we store those signatures in our smart contract.

- Player2 declares which coordinates they’ve shot at.

- Player1 signs all the “shot” coordinates, and we check if such a signature exists in our smart contract. No? That was a miss. Yes? A ship has been hit!

- Could Player1 sign the wrong coordinates and provide us inaccurate data?. Possibly, that’s why we verify the signature in our smart contract to make sure they signed the right data.

- Since we treat all shots as the same regardless of who shot it, could Player1 sink his/her own ships?. In this implementation, yes. We could make it otherwise, but I think a bomb is a bomb, regardless of where it blows. You decide if that’s a bug or feature.

Diving in

This is the source code of a smart contract in the Solidity programming language for our battleship game. For now, I restricted it to a two-players game, but with a little bit of work, it could support much more. Each player gets 10 coordinates (blocks) to form their ships. I think it would be best to envision the game as multiple states.State 1: Game start

- The smart contract gets deployed with a whitelist of player addresses allowed to play in that game. It makes it easier to track when all players have joined and the game has started.

- Players pick their ships coordinates, sign them, and send the signatures to the smart contract. Once they have done that, they have joined the game.

- When all players have joined the game, we’re off to the races. Players can not change their signatures (ship positions), nor can they take shots at this stage.

State 2: Game in progress. Turn in progress

- Turn 1, or turn 10, it doesn’t matter much. Each player can pick a single coordinate where he’d be shooting at. We store this coordinate in our smart contract.

- We make sure everyone has taken a shot before marking the turn as over.

State 3: Game in progress. Turn over

- Players retrieve all shots for that turn, sign them, and submit the signatures back to the smart contract.

- For each signature, we verify that the player signed the right data. If the signature exists in our list of known ships, it’s a hit!

State 4: Game over

- For a player to win, every other player must have lost all their ships. It’s a draw when nobody has any ships left.

If you’d like to follow along:

Find the repository on the Chainstacklabs GitHub and find the instructions: Game of Battleship Solidity and HardhatHeads up! It’s a TypeScript project, but if you’re not familiar with TypeScript, basic JavaScript understanding should be more than enough to follow along.Learn more about the differences between Sepolia and Goerli: Goerli Sepolia transition

Verifying digital signatures

Since all signatures created on Ethreum make use of the ECDSA curve, there have been suggestions to have a native compiled function for verifying signatures. However, that’s not yet available, and we have to roll our own solution. We need a smart contract to derive the corresponding address of the public key used to create the digital signature. We’ll be using the SigVerifier contract from the official Solidity documentation with some modifications.r, s, and v. We can derive these parameters from a signature by splitting it into the requisite number of bytes. Retrieving the public address from these parameters is as simple as invoking Solidity’s ecrecover function. This is a relatively costly process and consumes quite a bit of gas compared to normal transactions. To optimize the gas cost, we made use of assembly in our smart contract to split the signature.

We could also have split the signature offchain with JavaScript or another programming language.

The smart contract

- The game has a fixed number of players (two), each of whom can place 10 ship pieces on any coordinate.

- Players take turns shooting at their opponent’s grid by specifying the coordinates of a square. If a ship piece is on that square, it is destroyed.

- If a player loses all of their ships, the game is over and the other player wins.

- The contract uses the

SigVerifiercontract from theVerify.solfile, which provides functions for verifying digital signatures. - The contract emits events whenever a player takes a shot or loses all of their ships.

If you’re not familiar with EVM programming, mappings might seem an odd choice to represent our data model. However, to keep gas costs down and optimize UX, we want to avoid looping through and modifying large arrays in our smart contract.

players— a mapping of addresses to booleans indicating whether each address is a player in the game.ships— a mapping of each player’s address to a mapping of ship hashes to booleans. Theshipsmapping keeps track of which ship pieces each player has placed on the grid.destroyedShips— a mapping of each player’s address to an array ofCoordinatestructs. ThedestroyedShipsmapping keeps track of which of a player’s ships have been destroyed.playerShots— a mapping of each player’s address to aCoordinatestruct. TheplayerShotsmapping keeps track of the coordinates of the square each player has shot at during their turn.playerHasPlayed— a mapping of each player’s address to a boolean indicating whether that player has taken a shot during the current turn.playerHasPlacedShips— a mapping of each player’s address to a boolean indicating whether that player has placed all their ships on the grid.playerHasReportedHits— a mapping of each player’s address to a boolean indicating whether that player has reported all the hits from their opponent’s shots during the current turn.

joinGame— allows a player to join the game and place their ships on the grid.takeAShot— allows a player to take a shot at their opponent’s grid.reportHits— allows a player to report the hits from their opponent’s shots.isHit— whether a shot hits a ship and returns a boolean and the coordinate of the shot.destroyPlayerShip: an internal function that adds a destroyed ship coordinate to thedestroyedShipsmapping and checks whether the player has lost all their ships. If so, the game is over.

owner— the address of the contract owner.NO_PLAYERS— a constant that specifies the number of players in the game.NO_SHIP_PIECES— a constant that specifies the number of ship pieces each player can place on the grid.playersAddress— an array of addresses representing the players in the game.numberOfDestroyedPlayers— a counter of the number of players who have lost all their ships.isGameOver— a boolean indicating whether the game is over.

Going through the unit tests for the battleship contract will provide a lot of insight into its expected behavior, and how end users would interact with it.

Interacting with the smart contract

To be able to play a game with the smart contract, we need to create valid signatures that can be verified with Ethereum’secrecover method. It can be a little tricky to get signatures right with ethers.js, but here’s one way:

-

signShipCoordinates(ships: Array<Ship>, signer)takes an array of ships and aSignerobject (wallet) as arguments, and returns an array of signed ships. -

generateShipShotProof(player: Signer, allPlayers: Array<string>, battleshipGame: any)quickly generates a list of proofs for each reported shot coordinate.

"\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n" + length of the message. Taking a look at our SigVerifier contract, we hardcoded the length of the message to be 32. We do that because we always hash our messages and data, and the length of hashes is always 32 bytes.

Stats for nerds

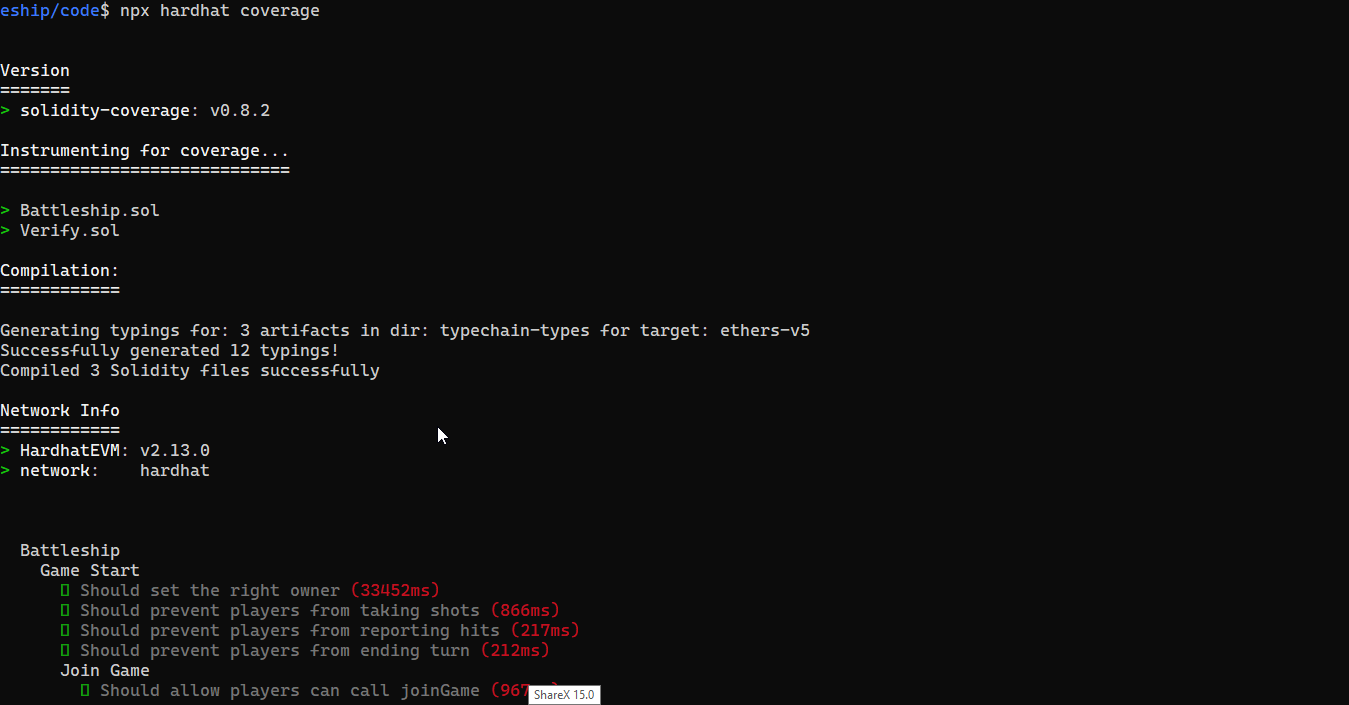

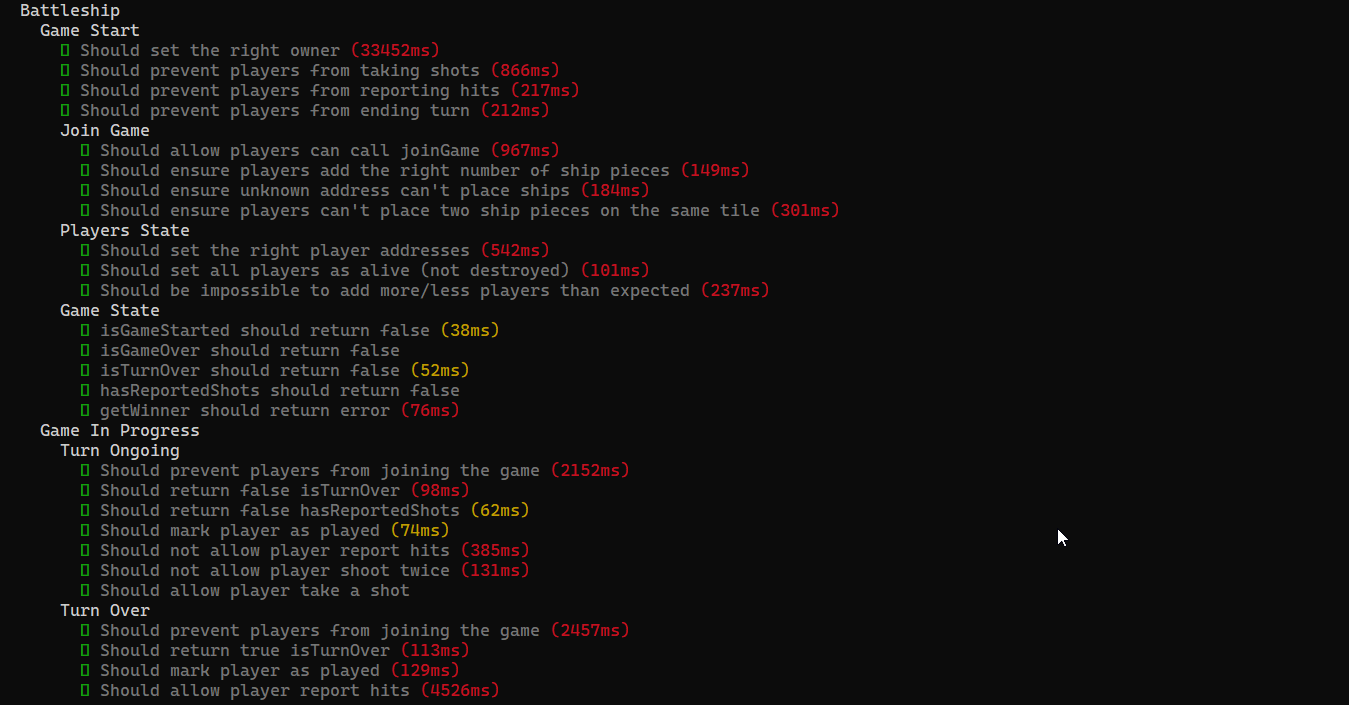

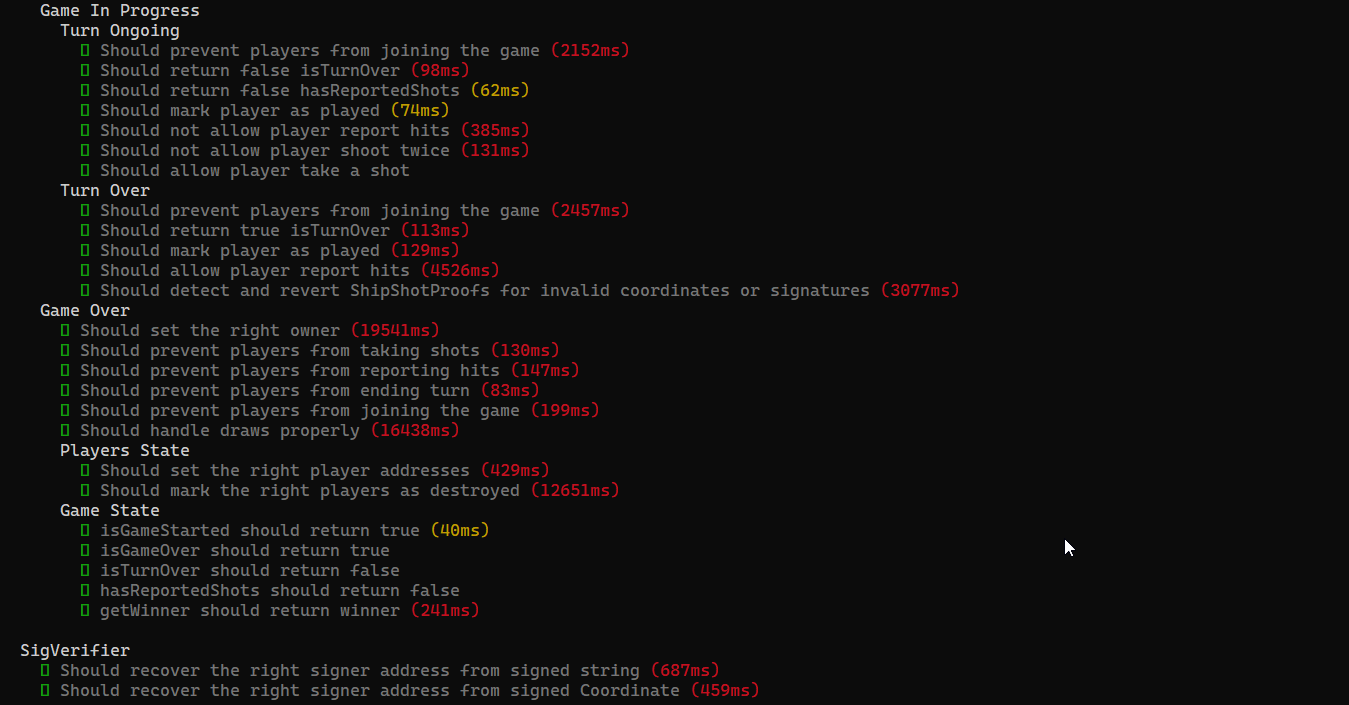

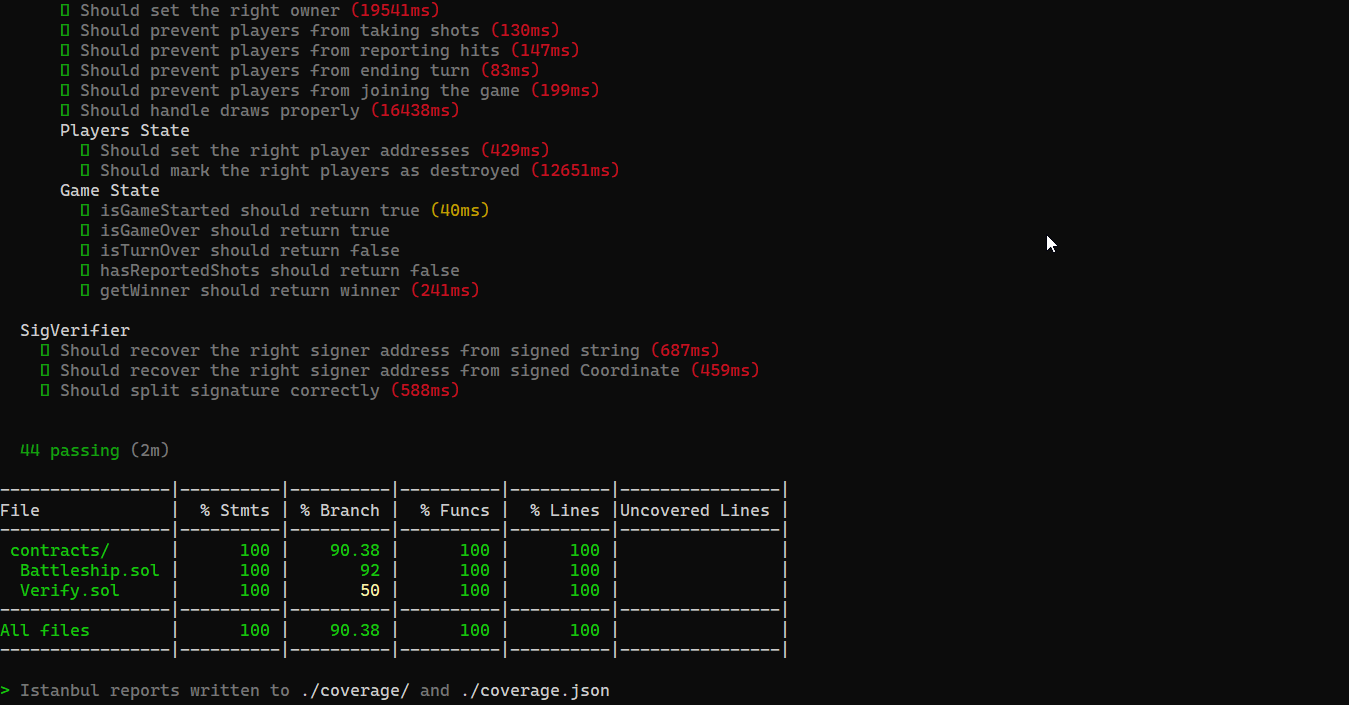

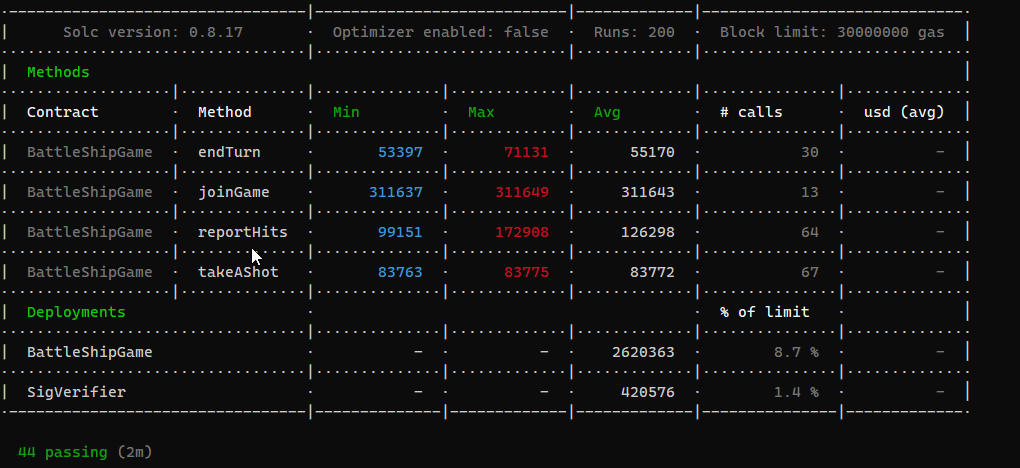

Here are some screenshots of the test case running through

joinGame is our most expensive function.

Conclusion

We’re finally done! We’ve built a complete game of incomplete information on a public blockchain. While we’ve built a game for recreation, these concepts could easily be applied to other ideas and projects. For example, we could create an anonymous NFT marketplace, where the owners of NFTs remain private, but they can verify their identity and sign off on bids.Further reading

Ethereum docs: Transactions

Smart contract languages

ERC-2098: Compact Signature Representation

ERC-1271: Standard Signature Validation Method for Contracts

Improvements

- We don’t actually restrict players’ ships to a board size. That doesn’t seem quite practical. To do this, we’d have to somehow prove the coordinates are valid, without showing anyone. While beyond the scope of this article, it is a valid use case for ZKPs. I created a circom circuit that does just that.

- We could add support for more players. We’d need to add a check to prevent destroyed players from being able to play.

- Using modifiers in the smart contract for tracking game state (

isTurnOver,isGameOveretc.). I chose plain reverts for simplicity. - Our game doesn’t yet have a UI. An interactive web UI would be a great addition!